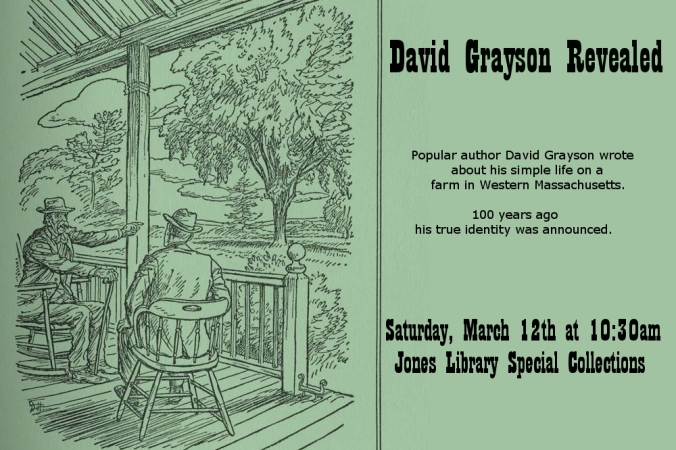

Below is the text of the talk I gave at the Jones Library March 12 on David Grayson, the writer of nine books on simple living that sold over 2 million copies in the first half of the 20th century. The true identity of David Grayson was a secret for 10 years, but 100 years ago this month, an Amherst resident named Ray Stannard Baker revealed that he was the author.

We are here to honor an Amherst writer who, a century ago, was more popular than either Emily Dickinson or Robert Frost. He spent a lot of time in this library, and although he’s not well known today, his books still have something important to teach us.

He used the pen name David Grayson, and a lot of readers were curious about who he really was. One hundred years ago this month, his true identity was revealed after 10 years of secrecy and speculation.

Our story begins in 1906, when the editors of a popular magazine called McClure’s were sitting around and panicking over what would fill the next issue. A desperate cry went out to writers for whatever they could contribute. One of them had been writing his private thoughts and experiences in notebooks for many years, never planning to publish them, and he answered the call.ik

He transformed these sketches into personal essays and invented the pseudonym David Grayson because it seemed like “a homely name that suited the subject matter.” He didn’t use his real name because he wrote hard-hitting journalism in the same magazine and didn’t want to confuse readers.

David Grayson portrayed himself as a well-read man who has left the city to live on a farm. He likes to walk around visiting people and meeting strangers. He patiently observes the ways of his rural neighbors, and shows respect for the humblest of citizens. In the words later attributed to Will Rogers, he never met a man he didn’t like.

The stories were a mixture of essay, philosophy, and quiet humor. They frequently cite the Bible, Shakespeare and Marcus Aurelius. They had a straightforward, colloquial style, and resonated deeply with people going through the challenges of industrialization and urbanization.

One reviewer wrote, “Those who read Grayson with sympathy and enlightenment are strangely conscious that here is a loyal, familiar and well-approved friend. Here is a man who has thought our thoughts for us, and who has given the soul of those thoughts their appropriate body in words.”

The author himself wrote much later that the stories “helped make people understand and enjoy their lives a little more deeply and fully, by presenting the beauty of neighborliness, the richness of the quiet life, and the charm of common things.”

The fictional David Grayson became a celebrity, and the actual writer admitted that he was a just a little jealous of his alter ego. Letters poured in to the magazine addressed to Grayson, and they are housed right here, in the Special Collections department.

One correspondent wrote, “Permit me, a humble clerk, to express my appreciation and thankfulness and tell you what an inspiration such writing is.”

Many of these letters will be on display here in Special Collections. My favorite of these letters came from George C. Baldwin of Springfield, Mass., who wrote in 1916, “To bring quietness to the heart in these days of storm, hopefulness in the heart of discouragement, sane practical wisdom into the fog of madness, and to do these with the sunniest, sweetest, most delicate humor, why, what could a man want more?”

Dan O’Brien wrote from Shanghai, where he was stationed on an American ship: “You have made me forget for a time that I was in a place where dreamers are not wanted.”

G. W. Elderkin of Pasadena wanted to know if the writer of “Adventures in Contentment” was a regular church-goer (he was not). Elderkin wrote, “He comes nearer to being a real Christian than anyone I know.’

Louis Eytinge of Arizona wrote, “Anytime you come out this way, drop off the trail and stop at my camp.”

Many of the letters came from nostalgic elderly people, students, men who missed rural life, and women with romantic fantasies. Many were addressed to “David” or “Dear Friend.” Dorothy Verall of Illinois wrote, “I wish if you are ever in Chicago that you would let me talk with you.” Another woman wrote, “David dear! Do you know how I love you? Take me with you when next you go on The Friendly Road.”

The David Grayson stories continued to appear in McClure’s, and later in the American magazine. They were collected in several books, such as “Adventures in Contentment,” which came out in 1907. “Adventures in Friendship” was published in 1910, the same year the writer moved to Amherst.

The publishers of the magazines responded to all the letters, saying that the David Grayson stories are “partly fiction and partly fact.” They wrote that the writer “lives on a small New England farm” and “as a letter-writer he is quite hopeless.”

David Grayson clubs sprang up, their members known as “Graysonians.” There’s a wonderful brochure from a Graysonian club that’s in a display case here. A Florida club wrote, “A true Graysonian will stop and retrace his steps to help an unknown brother find a lost bolt, and then drive out of his way to take this unknown brother home. He will give a hearty handshake when introduced to a stranger, and he will smile into the face of the sorrowing one with a smile of sympathy and understanding.”

Not everyone liked the David Grayson books. The misanthropic H.L. Mencken wrote, “Mr. Grayson’s sentimentality often descends to the maudlin. I fail to respond to his enthusiasm for yokels, his artful forgetfulness that the country is dull, dirty and uncomfortable, and that countrymen are stupid and rascally.”

There were ultimately nine David Grayson books, and they sold over 2 million copies. They were popular all over the English-speaking world, and one of them went through 40 printings even in Britain. They were translated into French, Czech, Norwegian, and even Braille. A magazine ad for his books called him “America’s most popular philosopher.” The president of the Mormon church bought 400 copies of “Adventures in Contentment” to give to members of the Tabernacle Choir.

There was a lot of speculation about who David Grayson really was. A similar literary mystery occurred in 1996, with the anonymous publication of “Primary Colors,” a cheeky narrative of Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign. That mystery didn’t last nearly as long as the puzzle of David Grayson’s identity, which has been called the longest-kept secret in modern literary history.

Some readers grew impatient. Dorothy Seward of Nebraska wrote to the publishers, “You are doing readers a flagrant injustice unless you tell them who David Grayson is. We can’t wait another year to find out. Some of us will explode!” A Seattle resident named W. H. G. Temple wrote to David Grayson simply, “Are you real or imaginary?”

There were at least six David Grayson imposters, one of whom convinced a woman to marry him by telling her that he was the famous author. It was an early form of identity theft. In Denver, detectives and newspapermen confronted a man who gave lectures as David Grayson, and showed him a telegram written by the real publishers.

In 1924, a man visiting an Arkansas town claimed to be David Grayson, cashed a bad check and disappeared. In 1935, a man in Indiana was involved in a car accident and gave his name as David Grayson, with an address in Amherst, Mass.

Other people, including a Maine writer named David Gray and an Atlanta attorney actually named David Grayson, issued statements saying they did not write the famous stories. One of Grayson’s books was called “Hempfield,” and many people thought it was written by a Hempstead, N.Y. writer named Walter Dyer, who tearfully maintained that it was not.

Charles Collins of Greensburg, Pa. wrote to the publishers suggesting that they offer a prize to anyone who reveals David Grayson’s true identity.

But by 1913, the secret was leaking out. The New York Post speculated, correctly, about David Grayson’s true identity. Geneva Smith of Frankfort, Mich. heard this rumor and wrote to the publishers, “Please tell me the truth about the matter. We can’t quite believe it. We think he must be a MAN of greater age and he must have lived that very life on the farm.”

The publishers responded with a non-denial denial. “The author of the David Grayson articles has never given us permission to reveal his identity,” they responded. “Of course, you hear all sorts of rumors.”

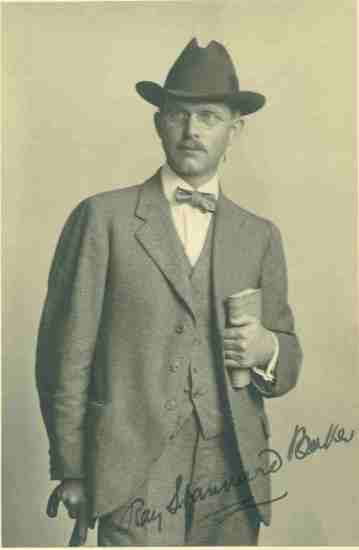

When Ray Stannard Baker admitted in March 1916 that he had written the David Grayson stories, ending 10 years of anonymity, many people couldn’t believe it. Baker was a well-known writer whose indignant, crusading style seemed far removed from the pastoral, gentle Grayson.

One of Baker’s daughters wrote that David Grayson fans would knock on the door of their house on Sunset Avenue to see if it was really true. Some were upset to find that Baker, unlike Grayson, lived in a town instead of in the country, and had a wife and family. “David Grayson has no right to have a daughter!” one said. It was as if David Grayson was the real writer and Baker was the impostor.

Book News Monthly wrote, “There was an apparent discrepancy between the character of David Grayson, the idler by woodland brooks, the poet of the open road, the philosopher of that deepest contentment in life which may be had by the lowest or the highest, and that of Ray Stannard Baker, the skilled journalist, the investigator thick in the hurly-burly of life and affairs.”

Baker was a worldly man. He had walked from Ohio to Washington, D.C. in 1894 with a group of protestors during an economic depression. He covered the bloody Pullman railcar strike that same year, and the McKinley-Bryan presidential campaign in 1896. He documented the exploitation of African-Americans in Georgia, who were arrested on trumped-up charges and sent to work on for-profit chain gangs. He interviewed socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs, meatpacking tycoon J. Ogden Armour, and inventor Thomas Edison. He was there with Guglielmo Marconi during the first trans-Atlantic radio communication.

But he had spent much of his childhood in a frontier settlement in Wisconsin, where he mixed with lumbermen, rogues and native tribes. He spent some of his early adult years in Chicago with very little money, perhaps contributing to his later empathy for people in distress.

In 1910, Baker moved to Amherst. It was actually his fourth attempt to get out of New York City and reclaim the rural life of his boyhood. Although he left Amherst to serve President Wilson during the first world war, he continued to live here until his death in 1946, which was front-page news in one New York newspaper. Baker’s brother Hugh was the president of Mass. Agricultural College, which became the University of Massachusetts, in the 1930s and 40s.

Ray Stannard Baker was a trustee of this library from 1929 until his death. He wrote most of his Pulitzer prize-winning biography of Wilson here, and much of the furniture in the curator’s office was originally his. Baker is buried in Wildwood Cemetery, but he made it clear that he did not want a tombstone. After titles such as “Adventures in Contentment,” “Adventures in Friendship” and “Adventures in Understanding,” when Baker died he had been compiling notes for a new David Grayson book to be called “Adventures in Mysticism.”

Baker wrote that during his arduous travels as a journalist, his life was pure toil, but writing the private sketches that became the David Grayson stories gave him release and joy. Coming to Amherst gave him the chance to live out the persona of David Grayson that previously he had lived in his mind only. He was an avid beekeeper and cultivated a fruit orchard, and kept hens. His book “Under My Elm” gives a detailed account of the economics of growing onions.

Here’s what Baker wrote about his double life: “Every man should have two occupations, else he cannot succeed, one by which he earns his bread, one by which he serves a greater purpose. I am a farmer, but I am also a reporter of life.”

Yet there is evidence that he wishes that readers had paid more attention to his reporting. He wrote later in his life: “At the time, I certainly felt that the articles I was writing under my own name were of far greater importance than the David Grayson sketches. I felt that I was reforming the world!” To explain why he separated his two personas, he wrote, “To confuse the issues with my adventures in such a different field seemed downright folly.”

So, was Baker a journalist who secretly wanted to be a farmer or a farmer who masqueraded as a journalist? Here I’ll quote from an address given by Frank Prentice Rand in this library on Founder’s Day 55 years ago: “David Grayson was no myth. He was a real man; indeed, he was perhaps THE real man. If anyone was wearing a mask, it was the journalist who rubbed shoulders with the celebrities of the day.”

Rand concluded his address about David Grayson with this: “His prescriptions, taken from nature and the great books, were not always profound. They may have been intuitive rather than intellectual, but they provided for hungry hearts and minds something in the way of rational uplift. If there is such a thing as salvation on earth, not only among men but among nations, and if there is such a thing as recovery from this feverish disease of modern life, certainly the way and the prescription are to be found in the books of David Grayson.”

This tribute to Baker appeared in the Amherst newspaper: “Like the bees he kept, Mr. Baker stored a wholesome sweetness. It is something for Amherst people to cherish that such a man chose to spend the best years of his life among us and to leave with us the rich heritage of his memory.”

This Saturday, the Jones Library in Amherst is hosting a revival of “To Tell the Truth.” I am participating in this program, which is about an immensely popular writer who was the center of a literary mystery 100 years ago. He was an Amherst resident who went by the name David Grayson, and he was a champion of simple living. Readers loved his books, but virtually no one knew who he really was.

This Saturday, the Jones Library in Amherst is hosting a revival of “To Tell the Truth.” I am participating in this program, which is about an immensely popular writer who was the center of a literary mystery 100 years ago. He was an Amherst resident who went by the name David Grayson, and he was a champion of simple living. Readers loved his books, but virtually no one knew who he really was.

![Helen_Nearing[1]](https://adventuresinthegoodlife.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/helen_nearing1.jpg?w=328&h=405)